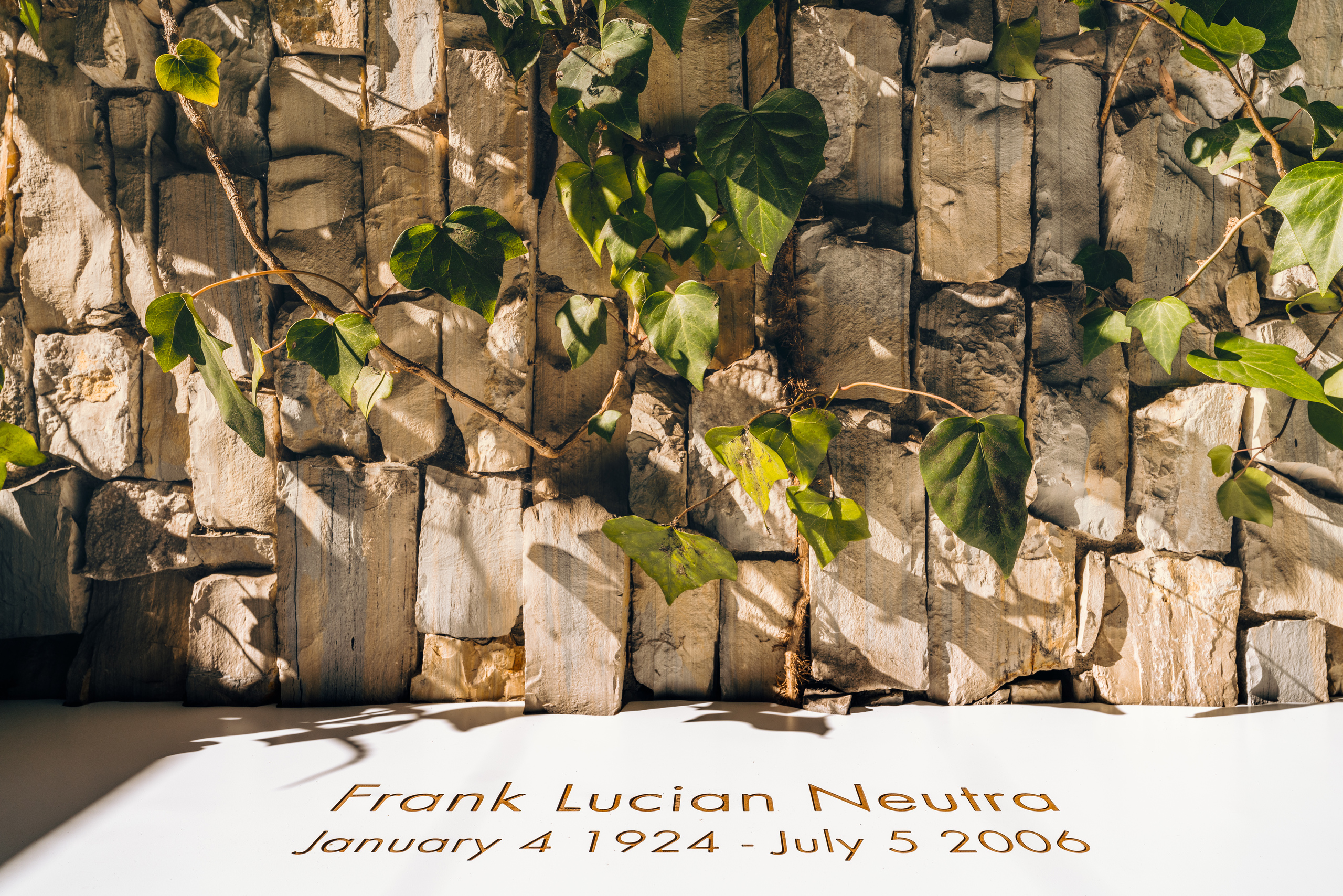

The Frank Lucian Neutra Memorial Bench for the exhibition "Built In" at the Neutra VDL Research House, Sept. 18 - Nov. 7

Frank Lucian Neutra was the oldest of three sons born to Richard and Dione Neutra. He was born in Hagen Germany in 1924 and died in Los Angeles at the age of 82. His ashes are in the courtyard of the family’s famous home along with those of his parents Richard and Dione Neutra. As a child Frank was diagnosed by his doctors as having “some degree of mental retardation and emotional disturbance.” Decades later his emotional and cognitive difficulties would be identified as Autism. The essay Frustration and Contentment: The Solitary Journey of Frank Lucian Neutra written by Frank’s younger brother Raymond gives a candid account of Frank’s life and the family’s imperfect efforts to understand and manage his disability. It is included with our piece for people to learn more about the Neutra family and to contextualize the memorial bench.

In October 2006, a few months after Frank’s death, the family gathered at the Neutra VDL House (by then owned by the Cal Poly Pomona Foundation) for Dion’s 80th Birthday and to remember Frank. The family placed his ashes across the courtyard from the bronze plaque that commemorates Richard, Dione and middle son Dion. They marked the location of Frank’s remains with a small, plastic laminated paper sign printed with his name that was thumbtacked to the edge of a wooden deck. Our bench, a “fitting” tribute to Frank, is sited on the deck in the courtyard of VDL next to the small sign bearing Frank’s name. We invite visitors to sit on the bench, read Raymond Neutra’s essay, and share in what Raymond describes as his brother’s “intense aesthetic pleasure in the contemplation of nature and his surroundings.”

Frustration and Contentment: The Solitary Journey of Frank Lucian Neutra

January 4, 1924 - July 5, 2006

By: Raymond Richard Neutra

On Sunday July 9, 2006 the following obituary was published in the Los Angeles Times:

“Frank Lucian Neutra died in Van Nuys on July 5th 2006. Mr. Neutra was the oldest son of architect Richard Neutra and his wife Dione. He was born in Hagen Germany in 1924 and joined his parents when they immigrated later that year to work with Frank Lloyd Wright after whom he was named.

Despite his parents efforts to overcome the barriers of autism he was never able to live independently. A gentle soul who derived his greatest pleasure from perfectionist drawings he spent his last years after his mother’s death in 1990, being well cared for in a residential facility. He leaves behind his younger brothers Dion and Raymond Neutra. The family will have a private memorial.”

I paid to have that short note inserted into the Sunday Times and arranged in October, after part of the family assembled to celebrate my brother Dion’s eightieth birthday, to have a memorial. With the acquiescence of Cal Poly Pomona, which now owns our family home, Frank’s ashes were buried by my brother Dion near those of his parents in the central courtyard garden of the iconic modern house where he grew up. The next night the family and his caregivers were invited to reminisce about Frank. In the partially lighted upper living room of the house, where the complicated electrical systems is slowly failing, I, my brother Dion, his two sons, his grandson and current and former wife sat in a circle and talked about Frank’s life in our family. A carload of caregivers apparently arrived late and knocked at the door downstairs pushed on the non-functioning doorbell without our hearing them and left disappointed. In this way the last chapter of my brother Frank Neutra’s life was brought to a close.

I came to realize that my grim determination, not to let Frank’s passing go unnoticed and to bring him back home and into the ceremonial center of the family was impelled by a deep feeling of grief. I projected on to Frank the loneliness that I would have felt in his place, extruded from his famous family out to a series of institutions and half way houses. If I were Frank I would have wanted to be remembered as part of that adventure and to have been allowed back home in the end. But of course Frank was oblivious to all those considerations. All he needed in life was a quiet place where he would be left alone where people would not ask him questions or touch him and would let him arrange the objects around him so that they exhibited a perfect order.

That being said, I feel the need from the perspective of a once apprehensive much younger brother, as a physician and as his last guardian to tell Frank’s story and the story of our family’s efforts to help Frank lead a happy life while at the same time meeting commitments to us other children and to my father’s crusading career to which our mother was so devoted. Since my parents had access to and availed themselves of the most sophisticated psychiatric and psychological advice, Frank’s story incidentally provides a window onto how American and European psychiatry approached children who today would receive the diagnosis of high functioning Autism, a diagnosis that was only formulated in the late 1940’s when Frank was already an adult.

Finally, reviewing all this, raises the following question for me: “What kinds of “good life” are available to people with the kind of cognitive, emotional and empathic deficits that characterized my brother and what kind of early education and experience would have best increased his chances of finding one of those ‘good lives’?”

In the last sixteen years of his life, Frank was surrounded by a community of care in the succession of intimate facilities where he lived. He gradually let go of the stern imperatives of perfection that had tormented him since his youth and settled into a life pattern that was mostly characterized by undemanding contentment.

It seemed that in these last years, spending the daytime hours at a sheltered workshop or in class activities and the evening hours in a home-like environment, he was able to look with a smile of delight at picture books and flowers, arrange his clothes on hangers, neatly and equally separated one from another by a few centimeters, initiate preprogrammed melodies on an electronic keyboard that I got him, or watch TV sitting slightly apart from the other clients. When I came to visit him during the earlier part of this epoch when he was more mobile, he would greet me in that hoarse voice of his “ HalIo Waymond”. I would ask if he would like to go out. “yas” he would say and then brush past me in his staggering gait on his way out to the car. We would drive up and along Mullhulland Drive in the Santa Monica mountains and he would smile delightedly out at the passing landscape. There wasn’t much point in initiating a conversation with Frank, questions to him were impositions that elicited a “yes” or “no” or a frown and a long painful pause followed by an echo of the original question. As we drove he looked out the window and studiously avoided eye contact with me. This contentment seemed to follow him even as the medical complications of old age multiplied and propelled him to ever more specialized care settings, finally landing him in a nursing home on Sepulveda Boulevard being fed a liquid diet through an in-dwelling gastric tube.

At our last visit, a month before he died, I sat next to him on a chair next to his wheel chair. After greeting me he fell into a contented doze.

Life was not always so filled with contentment for Frank, indeed frustration and even rage, directed at himself were the occasional emotions that changed the course of his life.

Frank was said to be a cranky baby. He was my mother’s first-born, delivered blue in the face with his umbilical cord around his neck, attended by a midwife at our maternal grandparent’s apartment in Hagen, Germany. It was a long traumatic delivery. When he was a few months old my naive mother was taken by surprise when the officials at the gangplank to the boat for America demanded to see Frank’s visa. She had assumed that her baby would be allowed to accompany her on her musician’s visa. However they declined to let her take him with her to join my father who had preceded her to America half a year before. With hardly a hesitation she handed Frank to her mother with instructions to bring him to his parents whenever his papers came through. My mother’s first love and priority was her brilliant husband who was nine years her senior. Her children were solidly accommodated in second rank.

Frank’s temper tantrums began in his first year of life when the order of his surroundings was disturbed or when his mother disapproved of something. If the telephone rang more than once, if the car made a turn instead of driving straight, if he was deprived of a comb, a shoe or a red cloth to which he was attached he would shriek and cry for hours. He related to no one but his mother to whom he stayed close as she moved around their part of Rudolph Schindler’s multi-family avant guard dwelling in Hollywood. He derived great pleasure from red flowers, which he would collect and he enjoyed beating time and humming the Bach pieces that my mother played on the Cello or sang. Although he was interested in books he did not speak and in the late summer of 1927 when he was three, he was taken to the Child Guidance Clinic in Los Angeles. This was more than two decades before the diagnosis of “Autism” was devised. Dr. E Van Norman Emery noted some degree of mental retardation and emotional disturbance and focusing on his language difficulties recommended that Frank be placed with an English speaking family. In January of 1928 when he was four he went to live with Mrs. Mary Moore and her family in Arcadia along with their two children and dogs, chickens rabbits and goats. In the interval Frank was seen by virtually every child psychologist in Los Angeles including Dr. Shepard Ivory Franz the head of psychology at UCLA and his assistant Dr. Grace Fernald. An academic building and a hospital now bear their respective names.

Frank stayed with the Moore’s until July 6, 1930 when he sailed with his mother and brother to Europe. My father joined them there after sailing to Japan and China and then to Europe through the Suez Canal. In her final note Mrs. Moore wrote presciently: “...anything that is mechanical Frank can do, and in time he could become very useful if some way can be found to teach him self control.”

The trip to Europe was frightening to Frank and his temper outbursts were so frequent that on arrival at his grandparents in Zurich he was placed in a series of institutions while his parents traveled on a lecture tour to teach at the Bauhaus in Dessau, to Brussels for the third Congress de Architecture Moderne (CIAM) and to the Netherlands to tour the production of architects like Oud, Duiker, Van der Vlugt, van Eesteren and Reitveld. In March 1931 Frank and my mother journeyed to Vienna where they consulted with my uncle, psychiatrist Wilhelm Neutra, who thought Frank’s problems were organic in origin perhaps due to his traumatic birth. Professor Poetzel at the University of Vienna gave a poor prognosis and recommended that Frank by institutionalized in Austria where they had specialized facilities. Sigmund and Anna Freud were also consulted. They believed that he was not feeble minded, but that the speech center and been injured. Since Frank was very attached to his mother the Freuds advised very strongly that mother take Frank back to America and keep him at home. In retrospect this was a lucky choice for Frank, who as mentally disabled and half Jewish would have been a prime candidate for euthanasia once the Nazi’s took over Austria.

My mother’s letters to my father from Vienna ( pp 214-216, “Promise and Fulfillment”) reveal the conflicting advice she was given and the turmoil in heart as to what she should do.

“I have tried to probe my soul which pulls me hither and yon. On one hand I would like to take Frank with me and take care of him. On the other hand, will I be able to manage considering my impatient makeup? Will he not completely usurp me so that I will have no time for you and Dion? Will I not be so exhausted in the evening that I shall lose all the musical skills I have regained through hard work? …and still, when he looks at me with such an adoring and loving expression, I imagine that his love for me, my understanding for him could be the key to helping him more than any doctor or treatment could. I would like to try to help him and would pray every night to find the necessary patience and insight to do this.”

“In the midst of my despair the entrance bell sounded and the maid brought me a little basked full of enchanting toys and a silken housecoat with the most loving note from Mrs. Freud and Anna Freud. Is that not touching?

“I am back in Zurich. I have suddenly found an inner equilibrium that lets me endure all outer difficulties and agitations with unruffled equanimity.”

On returning from Europe Frank attended a series of schools, could do well at arithmetic, play the piano but had difficulty reading and had tantrums when he failed at something or when his younger brother Dion or the children at school teased him.

Dion remembers Frank as passive and docile, an easy accomplice in adventures initiated by Dion that sometimes got them in trouble. Once while digging a cave for themselves, the dirt caved in around them but they managed to dig themselves out. Another time Dion threw a rock that hit the glass of a fire alarm box. As the wandered back home the looked down the hill to see several hook and ladder trucks clustered around the box. Dion was often blamed for triggering Frank’s tantrums and this helped define his family role as the mischievous and misbehaving child. Thus Frank loomed large in his childhood. The early 1930s were financially challenging for my parents but were also a time of architectural innovation for my father and he was busy in the suite of rooms in our house that served as his office. He left the raising of Frank and Dion to my mother.

In a letter to Anna Freud in on December 20th 1935, my mother describes how the 11-year-old Frank developed a series of automatic behaviors, holding his breath and hopping downstairs on one leg and switching the light switch on and off twice when he reached the bottom. He consulted his watch and screamed when the family did not eat dinner on time. She wrote further: “During walks no one should talk; when he comes to a tree he holds his breath, hops again, touches the tree twice quickly, exhales loudly and looks at his watch... When he read a book or when he read a sentence and made a mistake, he did not want to continue, but always wanted to start from the beginning, clicking his tongue and making special finger movements.. This he does not do anymore. It is indicative for him the he starts such Ticks and then gives them up again and the starts a new one. He absolutely wants to become a 100 years old. He knows the calendar and has figured out for himself how many days there are in a thousand years. He asks many questions, for instance: why do fish have no arms and legs, do they have teeth? He still cannot answer a question.”

It seems that Frank could understand what was said to him when the topic caught his interest. I confess that by the time I came to interact with him in our adult lives I never found what such a topic might be. He could initiate a line of conversation but was stymied when challenged by another’s question. This made verbal contact difficult. In all the years I knew him, I never heard Frank laugh. Laughter requires a particular kind of insight that Frank did not have.

Anna Freud wrote back to my mother a few months later on a March 10 1936:

Dear Dione Neutra, I admire you that you continue to carry this heavy burden of keeping Frank at home. I am afraid that you may not be able to keep it up. When Frank reaches puberty, there may be a time where it will be impossible for you. But perhaps until that time one can still help him. He must have made great progress in his speech as I notice from your description. The new symptoms, which you describe, are all compulsion symptoms. I believe one has to assume that they always happen when he was fearful. The task is to conquer this fear. Perhaps you can dissolve them when you speak with him about this fear, which must have happened before the Tick started. Apparently when he reads, he is afraid that he will not be able to finish the sentence, and then he starts with the clicking of his tongue in order to conquer that fear. Why don’t you observe him in this respect? But here always remains the question: Which is more disturbing- fear or the compulsion symptoms? I am sorry that I am so far away and cannot help you.

With Warm Regards,

Yours Anna Freud.

They were encouraged to enroll Frank at the Bosca School in Pasadena, which had one teacher for each five students. He stayed there except for weekends until 1940 and made academic progress ultimately reaching a 5th grade level in arithmetic. Once when left for a piano lesson near our home in the Silver Lake district of Los Angeles on the weekend he was asked if he could walk home. He enthusiastically said yes, and when he did not appear home after the lesson my parents were deeply concerned. Finally late in the evening the Bosca School in Pasadena called to say that Frank had arrived there. He had noticed the ten-mile driving route from Silver Lake to Pasadena and happily accepted the challenge to walk “home” on his own.

Between 1940 and 1946 Frank lived at home working as my mother’s housekeeper. He was at home, not hidden, and part of our family life. My playmates accepted him as he was and did not tease me about him, nor do I remember being ashamed of him.

Around that time a young psychology student Murray Jarvik (who later himself became of professor of psychiatry at UCLA) was engaged to tutor Frank. They were both in their twenties, and Murray remembers how Frank took the bus by himself from our Silver Lake home to the area near UCLA where my grandparents lived and where his tutoring sessions took place. Frank was a whiz at arithmetic, but spoke explosively and with difficulty. Murray, who as I write, is in his eighties, cannot remember how he came to have this tutoring assignment or what theoretical framework governed his approach to my brother, which was primarily cognitive in orientation. When my parents returned after a six-week trip they were astonished at the progress Frank had made. He could speak for fifteen minutes about little trips he had taken with his young teacher.

My childhood memories of Frank go back sixty years to that time in the mid 1940s when I was nine and he was in his early twenties. In those days, before General Motors dismantled the web of streetcars that cris-crossed the Los Angeles basin, Frank was able to go by himself to the County Museum in Exposition Park to look at the exhibits. He read the captions about billions of stars. He could play the piano after a fashion and drew realistic pictures of flowers with colored chalk. He had regular housekeeping duties.

In each of these activities he had strict internal standards and if these were not met or if others showed even a hint of disapproval it unleashed a hoarse crescendo of grumbling and then shouting and even jumping, running and head banging. I have an image of him pelting along the sidewalk in front of our local market and, when coming to its end, leaping into the air and landing in a squatting position in the dirt beyond with an enraged shout of complaint: “ I didn’t do OKaaaaaaay!”

Between 1946 and 1950 a former teacher from Appalachia, Roberta Walen, came to work as our housekeeper. I remember her as a big boned friendly freckled woman with graying hair who used to tell me stories about her former students the “swamp angels”. She took a special interest in Frank and participated in the therapies proposed by two speech pathologists Edward and Mary Longerich who hoped to entrain brain cells in Frank’s right brain undamaged by the traumatic blue-baby home birth twenty years before in Hagen Germany. This they would do by getting Frank to use his left hand and by play acting, writing short stories and consuming Glutamic Acid to “stimulate his parasympathetic system.” They were but the latest of specialists that my parents had tried in hopes of restoring Frank to normalcy.

Roberta felt that my parents were treating Frank as a household drudge and that with help he could go on to college. She encouraged them to buy him clothes appropriate to a young man of his age. A photo from the time of Frank in coat and tie with brilliantine in his hair, a handsome young man, must date from this time.

Roberta worked daily with Frank on various academic subjects. My mother was dubious of her methods and aspirations for Frank but grateful that someone was so dedicated to his welfare.

Frank began to chafe at the household tasks and to be frustrated with his lack of progress he was “trying so hard”, “stiff in the brain”. His temper tantrums became more frequent. In March 1948 soon after beginning a hot pack treatment prescribed by a chiropractor, a Dr. Strober, my mother wrote in her diary: “Frank and Roberta were alone in the house. While she was washing the dishes, she heard a noise in the playroom and asked, “Is anyone there?” Frank answered, “ It is me”. She was surprised and asked, “Why do you sit in the dark”. She later did not know for certain that to Frank this remark was a reproach, but it sparked his apparently already wrought up emotions. He slammed the door, ran upstairs and started to shout that he wanted to kill himself because he now realized that he was no good. He kept this shouting up for two hours. I asked Roberta whether she attempted to pacify him? To my horror she replied that she was not feeling well, was afraid of him, that she might have a heart attack, so she went for a walk, thinking he might come to his senses in the meantime and he was left alone for an hour. When she returned all the neighbors had assembled and had called the police. She told them that Frank was not dangerous and apparently Frank had quieted down and gone to bed.”

This episode lead to Frank’s referral to the Devereux school in Santa Barbara. Roberta wrote her impressions to the school:

“..I recommended some better clothes to wear when he went out. Mrs. Neutra very cheerfully far exceeded my expectations and pride began to develop in Frank. He became interested in harmonizing his outfits. In a remarkably short time he was playing selections from Handel, Haydn, Beethoven, Schubert and Bach. He was so proud the night of a recital program in which he performed, while his family listened. My idea was to lift his all but submerged ego to a fraternal nearness with his family. Still later he drew pictures and if the mother in me can discern he was deeply moved at his father’s interest in these studies, which you have there at Devereux. But he was so very timorous and so sensitive that a facial communication, tone, eyes a few shock words such as “look”, “listen”, “please” etc. and others would throw him into a panic… He loved the mountains, the sea, the well ordered dinners we sometimes had in restaurants; learned to order for himself or finally too, he learned to help me from street cars and buses when I was lame, he learned to guide me through traffic .. I being hired to cook felt myself at a social disadvantage in pressing my points. …If someone there, great-hearted can possibly reach out to him they will discover a fine person who can be taught possibly “to stand among men” to use Frank’s own words.”

Roberta must have instructed Frank on how to help her, probably the only instance when someone tried to purposely coach him in actions that would make up for his congenital lack of empathy for the needs of others.

Between 1948 and 1950 Frank was in and out of institutions. I remember a nighttime visit to the Deveraux School in Santa Barbara in 1948. The patients were gathered around a bonfire and I retain my feelings as a nine year old of moving among the shadowy strange scary people. In July 1949 Dr. Fernald saw Frank again. At that time Frank’s reading was at the Sixth Grade level. With regard to emotional response Fernald stated:

“When we first knew Frank he was an infant of four or five years of age, under the supervision of Dr. Shepherd Ivory Franz. At that time his speech was almost entirely undeveloped and his responses were decidedly infantile. We do not have the record of Dr. Franz’s tests and experiments during that period. By 1938, when he was fourteen years old, speech was developed so that he expressed himself freely, though somewhat jerkily and in a high pitched voice. By 1949 his speech was quite fluent. There is a tendency to continue along a given line of thought without regard to the background or to other people who may be involved in the discussion. Frequently associations by similarity without regard to the content determine the course of conversation. As a child Frank was tense and excitable and given to hysterical outbursts when blocked. During the recent tests he became very excited, pounded the table, said “I must do better; I must get it right!” clenches hands, puts them to his head and so forth. This occurred twice during tests. Frank then quieted down and proceeded with the tests. It is evident that he is extremely anxious to do well, and very much disturbed by any idea that he is failing. Perhaps the most interesting thing about Frank is the irregularity of his performance. At times he will suddenly pick up the thread of a test, and show capacity beyond that which he had formerly seemed able to do. For example, at the Average Adult level, in the last test, he did the Arithmetical Reasoning test correctly, and with little effort. There is an evident disintegration which is increased by a rather frantic effort to do well.”

Back at home the tantrums continued, in one he destroyed his bed and the police were called. I was away at boarding school for many but not all of these tantrums. Indeed the greater affluence of my family by the time I was born allowed my mother to solve the conflicting demands of my father’s career, of Frank’s needs and my need for a structured predictable environment by finding a good boarding school and I actually thrived happily there. On March 11, 1950, when Frank was 26 and a day before my eleventh birthday, Frank was admitted to the state hospital at Camarillo, I was secretly relieved.

For twenty years, between 1950 and 1970 Frank was at Camarillo, interrupted in the late 1960s by a stint at another state hospital when he was treated for tuberculosis. During this time he also developed seizures. Like virtually all institutionalized patients in those days he received many courses of electro-shock therapy. For a period of time the superintendent Dr. Nash who was a client of my fathers arranged for him to have a private room, but after Dr. Nash’s death Frank was returned to the 80-man ward and the 150 man day room.

During this time period I was away at boarding schools, college and medical school. As I recall it my mother or both my mother and father would visit Frank every few months. I was along on some of these visits and remember the red tile roofs, pleasant landscaping, white walls and large sterile rooms and their wandering inhabitants. Men in white suites with large key rings would open the door with a clang to allow a grinning Frank to hurry out to meet us. In answer to our formulaic questions: “How are you Frank?” or “What are you doing these days” he would answer, “I’m fine” or “I am doing OK."

After my father’s sudden death in Germany in April of 1970 my mother called me long distance and tearfully asked if she could stop over in Boston where we then lived and take the time to visit a special school in upper New York. Now that her duties to my father were over she was determined to get Frank out of Camarillo State Hospital. We drove across Massachusetts to visit the school but my mother eventually decided it was too far from California and instead she arranged for Frank to be transferred to Topanga West Guest Home in Canoga Park This was a drab dormitory-like facility smelling of tobacco and filled with loitering middle aged clients, one of whom served as Frank’s roommate. However, Frank was free to take walks in the neighborhood or visit nearby stores. He had lost a great deal of ground during the twenty years at Camarillo. He read and did math at a third grade level and hardly initiated any conversation at all except during his tantrums when he would say “ “I did wrong ten thousand years ago!” But these tantrums were infrequent perhaps as a result of the Phenobarbital he took to prevent seizures.

For the next twenty years, on the weekends when she was in town, my mother would drive out to pick up Frank and bring him to our home in Silver Lake to spend time there, where they would watch Nature TV shows or she would bring Frank to concerts. He would walk around the lake. Frank had a part in her life but she did not devote herself to him as she had to my father. She said it made her happy to see his smile when he looked at the picture books. I think she thought she was rescuing him, at least for the weekend, from a place that was not much to his liking.

Around this time Joyce Pelka, a psychology student who was working at Topanga West wrote a long case study about Frank drawing on documents, now lost, that my mother provided her. Much of this account relies on her report.

An art therapist Peggy MacDonald, who coincidentally had taken a course I ran on Neutra houses for the Los Angeles School district in 1960, became interested in Frank while giving art classes there and often took him to her home and on little outings.

Toward the end of the 1980s I arranged for Frank to be supervised by the California Department of Developmental Services Regional Center so that there would be a continuity of supervision for him that would continue even if no family member survived.

At the suggestion of the Regional Center Frank began attending the New Horizon’s school and sheltered workshop, which sent a bus to collect him in Canoga Park.

On September 1, 1990 my mother died in her home at age 89. I flew down to Los Angeles and drove out to Canoga Park to inform Frank. He accepted the news impassively and I explained that he would no longer be spending the weekends at Silver Lake since mother was no longer there, and the house would be given to Cal Poly University. After I left Peggy MacDonald happened to visit Frank and ask him how his mother was. “She is at the University,” he said.

Life continued for Frank as before. He did not seem to miss the weekend sojourns with the mother to whom he had been so attached as a child and from whom he had been separated so many times.

Around this time the caseworker at the regional center suggested that Frank be moved to another facility run by the Philippine nurse Espi Grana. Two Philippine attendants, Isabelle and Angelito Menor, lived in a pleasant Van Nuys ranch house, which was set up to deal with medical problems of people of Frank’s age. They cared for Frank and five other elderly clients. When my wife Penny and I visited we were charmed by the kindness of the attendants and the lovely garden and quiet neighborhood.

With some trepidation about the routine-addicted Frank I arranged for the transfer. When the bus came to take Frank to New Horizons I arranged for movers to transfer Frank’s things to his new dwelling, and made sure that all his clothes were hanging with the requisite half inch separations and all his things arrayed on his new desk. I picked Frank up at New Horizons and brought him to his new place, expecting an angry frown and a tantrum, but he checked out the closet and the layout and accepted the change without comment.

As Frank’s guardian I would consult with the regional center caseworker by phone and would visit Frank when I flew south to Los Angeles. On his January birthdays I would send him a bouquet of red roses, one for each year of his life. Apparently these gave him pleasure.

In the last decade of his life, as I have said, the tantrums and frustrations about his abilities slowly diminished, and Frank achieved a kind of tranquility. His attendants seemed genuinely fond of Frank who kept his room so neat, himself well groomed and who kept happily to himself and never was unkind to anyone else. At the sheltered workshop he worked slowly but meticulously and with a smile as he packed medical items into plastic bags.

In retrospect, access to the social security payments as the disabled child of my father and to the resources of the regional center of the California Department of Disability Services afforded Frank in the last decades of his life a kind of autonomy, a level of expectation and a kind of care that were perfectly suited to his needs.

To be candid it also allowed my mother and then me as his guardian to assure that his needs were indeed met without making Frank the center of our family with all the practical and emotional ripples that his presence there would have produced. During the time after my mother’s death my own nuclear family was sequentially coping with a quadriplegic stepson and then a wife with Alzheimer’s disease. These social programs gave Frank the ability to leave the nest and his family the ability to cope with its residual problems.

My well-connected family availed themselves of all the expert and not so expert advice they could think of to help their quirky, demanding and unhappy child. In a note to the Deveraux School, and after the unhappy explosions caused by Roberta Walen’s ambitious efforts on Frank’s behalf, my father wrote:

“No one should be trained or conditioned to harbor aspirations or ambitions beyond his capacity. Especially an evidently handicapped person should be only very gently guided out of the realm where he can handle things, processes and human relations with ease...He must get out of his introversion and made to love to do like other people do. Not talk aloud to himself, not shout and yell with open windows, not to make his bed meticulously for one hour and a half-because other people also do not do any of these things- so he should also not do it. All this will not improve Franks physiological deficiency; it will merely adjust his social life so that he can stay with us and be fairly happy… or if we die and he is left in this world with others to accept him and to be friendly.”

Despite the cognitive progress that specialized attention was able to give Frank, despite the progress that he made in acquired life skills, all that progress was not enough to outweigh his inability to manage the anger and frustration which he felt when he failed to achieve his goals, the goals that other’s set for him or when the world did not present the order that he desired from it. In the end he was happiest in a setting that made little or no demand on him.

The the various psychologists and psychiatrists who focused on cognitive skills, skills of everyday living and restoring Frank to a normalcy must have been guided by the unspoken goal of creating a life that was useful to society. Even the most humanistic and caring of psychologists in the 1920’s and 30’s would have been aware of the Eugenicists and Social Darwinists to their political right, who in those decades were sterilizing mentally challenged young women in the United States and actually euthanizing them in Germany to protect society form an imagined epidemic of unproductive members. Today we accept (if we do not adequately fund) the duty to compassionately care for clients and assist the families of those who simply will never be productive members of society.

It seems that none of the experts who advised on Frank’s special educational needs addressed the problem that Mrs. Moore pinpointed in her final note of 1930: The need for self control, the need for techniques or medication to manage the rage he felt when things did not go the way he expected them to. These days there are behavioral interventions with family and “clients” that carefully assess the family dynamics and triggers for anger and provide interventions for the client and for the family. These increase the chance of managing raging emotions in ways that don’t require confinement. Perhaps a young adult like Frank would today find life in a suitable halfway house and sheltered workshop instead of the state hospital.

My parent’s attempts to respond to Frank’s musical and artistic tendencies with formal music and drawing lessons may have reflected their respect for the creative life, even if such a life was not highly prized by society. But here they had high standards. “Surely”, they may have been thinking, “if he gets aesthetic pleasure it would be greater if he had a chance to challenge himself at a more refined artistic level and realize himself more fully even if it had no interpersonal or social value.” However because he could not manage his anger, in the end it was doing humble things of no value to anyone but himself, like the meticulous shadings in his coloring books, doing 1000 piece jig saw puzzles or making his bed that made him happiest.

Martin Seligman has said that authentic happiness depends on a balance between a pleasurable life, an engaging life and a meaningful life. For Frank there were intense aesthetic pleasures in the contemplation of nature and his surroundings, he became engaged when drawing and assembling jig saw puzzles and when making his bed with great perfection, but the satisfactions of doing something of meaning for others, even when coached to carry them out in a mechanical way, was beyond him.

As I write this, and considering his glimmerings of special talents and sensitivities, I ponder whether there was any course of education in which Frank could have “stood among men” as Roberta Walen had hoped, or that would have allowed him, in his solitude to intensely push his own signal strengths as an artistic or musical savant to their full potential? The ability to do this requires an ability to withstand the pain of the many inevitable little failures that all creative people face. It also requires a drive toward a formulated personal goal step by step. While Helen Keller relied on Anne Sullivan for much of her lifetime to get through college and write her books it was Helen, who, with an iron will set these goals for herself and who overcame the frustrating obstacles in her path. Could Frank, even with the prodding of an ambitious Roberta Walen have ever done this without being tormented by the failure to meet his own solitary high standards? Could he have done this without exploding and precipitating the need to confine him?

Given the right cognitive and practical skills and the techniques for emotional self-management, given access to some ongoing coaching, what kinds of good life, if any, might Frank have found for himself? These unanswered questions haunt me.

In the end, with the help of his caretakers he achieved my father’s more modest goal for him: to be directed by others to a fairly happy, if socially unproductive life and to be with others who appreciated his spells of blissful absorption, his acquired life skills and his lack of guile or malevolence. They accepted him with a friendship and a kindness he did not visibly reciprocate.

Reformatted and reprinted for the fall 2021 Neutra VDL Studio and Residences exhibition “Built-ins” with permission from Raymond Neutra.

This essay accompanies our bench acknowledging the life and remains of Frank Lucian Neutra designed by TOLO Architecture.

Press:

Wallpaper article: "Last chance to see: a ‘house party of a group show’ at Neutra VDL House in LA" by Pei-Ru Keh on May 30 2021

Metropolis article: "A New Group Show at Neutra’s VDL House Remembers Those Who Lived There" by Jessica Ritz on September 21, 2021

Dispaches article " Domestic Bliss “Built In” at the Neutra VDL House" by Zara Kand on October 15, 2021

Work

Office

Work

Office